If you’ve ever hiked at Smith Rock or boated at the Prineville Reservoir, you were recreating on the rim of an ancient supervolcano—the remains of which are now called the Crooked River Caldera. Central Oregon may have once looked a lot like Yellowstone, and with a little geological know-how and a keen eye, the evidence can be found all around us. So first, a little bit of a geology lesson!

A supervolcano is big. Really big.

A volcano is bestowed supervolcano status if at any point in time it erupted more than 240 cubic miles of material. For comparison, Mount St Helens erupted just 0.3 cubic miles of material in 1980, causing ash to fall as far away as Minnesota and Oklahoma. A supervolcano’s magma chamber builds very slowly over time, causing the earth above to swell, until the volcano erupts with such destructive force that it leaves behind a large depression or caldera.

The original kind of hotspot

You may have heard that Yellowstone National Park sits atop a supervolcano or, more precisely, what geologists call the Yellowstone Hotspot. A hotspot is a stationary plume of extra hot magma from deep in the Earth. It melts the Earth’s crust from below, resulting in a breadcrumb trail of volcanic activity on the surface as the continental plates drift over it – like drawing a dotted line by holding the pen stationary and moving the paper. Geologists have been able to collect enough evidence to piece together the historical path of the North American plate over the hotspot currently crowned by Yellowstone. Locales of note along this path include the Snake River Plain in Idaho, Owyhee Canyonlands, and our very own Crooked River Caldera.

Caldera-spotting

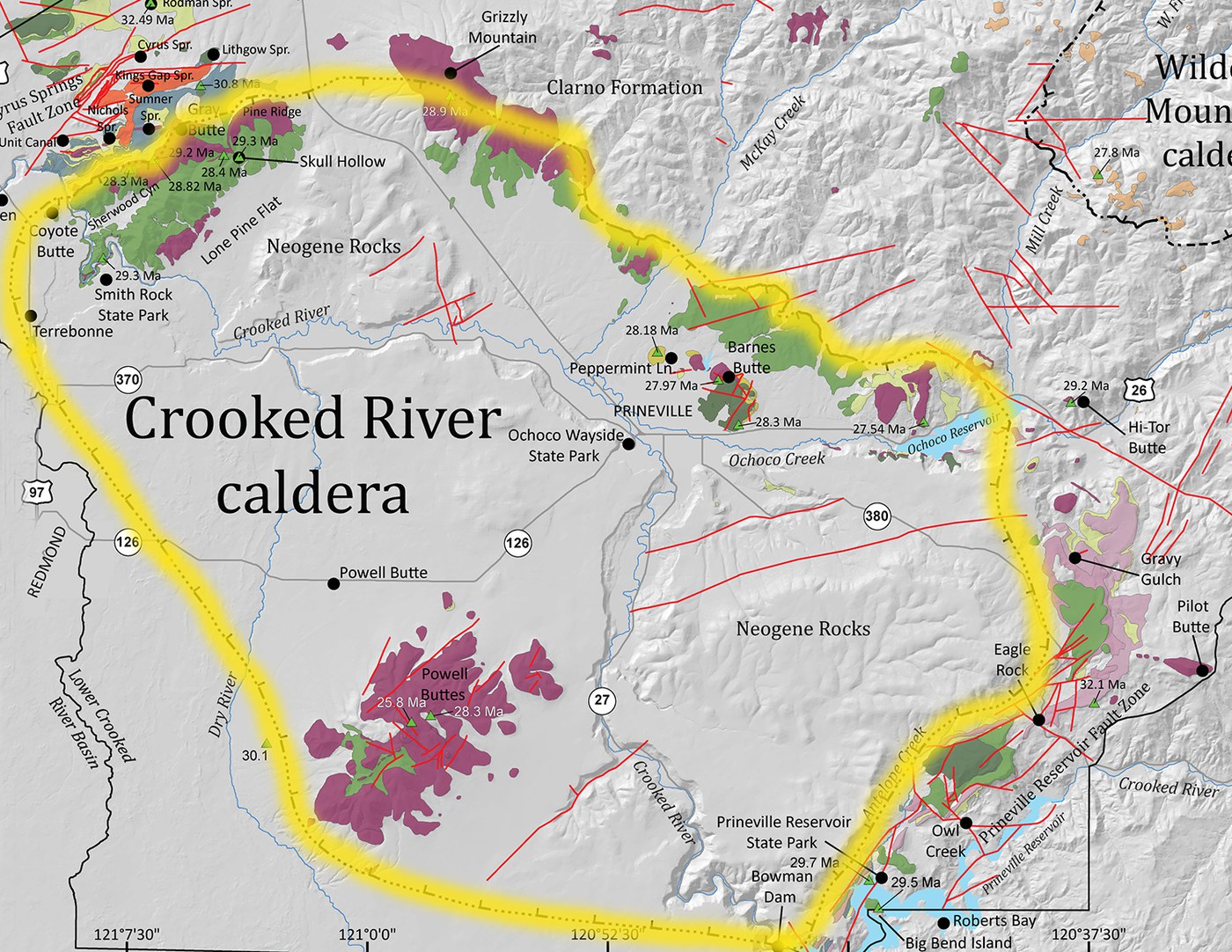

Visual evidence of the ancient supervolcano that formed the 26-mile long and 17-mile wide Crooked River Caldera is peppered around our Central Oregon communities—much of which could be explored in a single day’s drive. Believed to have been formed around 29.5 million years ago, the caldera is a semi-elliptical shape with Terrebonne, Powell Butte, and Prineville near its perimeter. The following are a few places in Central Oregon where geology enthusiasts can readily spot evidence of the caldera we live in and around.

The rocks are crooked too, not just the river

Prineville Reservoir Boat Launch and Peter Skene Ogden State Scenic Viewpoint are both great spots to view the very edge of the caldera. We’re going to get a little technical for a second here: the principle of original horizontality in geology states that due to gravity, rock layers (called strata) are always initially deposited in nearly horizontal positions. This means that if we see rock strata that are steeply angled, outside disturbances (like volcanic eruptions in this case) moved them into that position after they formed. Standing at the Prineville Reservoir boat launch looking across the water, you can see a tall rock formation exhibiting steeply inclined strata tipping to the northwest. This is evidence of the rock layers tipping in toward the center of the caldera when it collapsed. Another example can be seen when looking at Smith Rock from the old highway 97 walkway at Peter Skene Ogden State Scenic Viewpoint. The southeastern-dipping ridge of yellow hoodoo-like protuberances emerging from the graceful rounded slopes pre-date the caldera eruption. Geologists believe the ridge dipped toward the caldera center when it erupted, resulting in its present-day angle.

A ring of rhyolite

Rhyolite is an igneous rock formed from molten lava that is high in silica and very viscous—the type of lava that builds up and explodes in pyroclastic eruptions rather than gently bubbling out. Rhyolite domes are often found outside the ring fracture (the fracture along the perimeter) of calderas after their formation. The margin of the Crooked River Caldera’s ring fracture was populated by rhyolite domes which we know today as Grizzly Mountain, Barnes Butte, Powell Buttes, and Gray Butte. Hiking these buttes can afford expansive vistas all the way across the caldera.

Visiting any of these locations is enjoyable purely for the natural beauty and enjoyment of the outdoors, but when we view them through the lens of geology, stories and history unfold that can turn a rock into an item of intrigue and curiosity.

Sources:

- USGS: What is a supervolcano? What is a supereruption?

- USGS: How much ash was there from the May 18, 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens?

- USGS: Mount St Helens ash eruption and fallout

- National Park Service: Volcano

- National Geographic: Hot Spots

- Geology of Central Oregon: Crooked River Caldera

- National Park Service: Geologic Principles—Superposition and Original Horizontality

- Oregon Geology: Field trip guide to the Oligocene Crooked River caldera: Central Oregon’s Supervolcano, Crook, Deschutes, and Jefferson Counties, Oregon

- Miller, Marli B. Roadside Geology of Oregon, Second Edition. Missoula, Montana, Mountain Press Publishing Company, 2014.

Sarah Graham is an Oregon State Certified Master Naturalist who spends her free time mountain biking, trail running, talking to plants, and learning about all things nature.

Sarah Graham is an Oregon State Certified Master Naturalist who spends her free time mountain biking, trail running, talking to plants, and learning about all things nature.