by Sarah Mowry

The temperature on the dashboard of the car hovered at 99. The heat waves danced on the road as we came up the long driveway at Rimrock Ranch. It was one of those early summer days when anything above 80 seems extreme, and you’re sure the rattlesnakes will be sunning themselves everywhere you look. Perfect time to tag along on a kestrel banding expedition!

For nearly 25 years, Don McCartney and his team of dedicated volunteers have been braving temperatures like these—and probably a few snowflakes in between—all for a beautiful, fierce little bird called the American kestrel. Kestrels are the smallest and most colorful raptor in North America. They are similar in size to a mourning dove, and the males have slate-blue heads and wings that contrast with a rusty-red back and tail. Kestrels are skilled hunters who need the open sagebrush meadows of Central Oregon to hunt for their main prey, Western fence lizards.

This “monitoring” is not for the faint of heart or for those short on time. Volunteers must check the boxes three times in late spring and early summer, oftentimes climbing tall ladders (or trees!) in remote locations. Their job is to establish whether or not kestrels have chosen to nest in the box, determine when they lay their eggs, see if they hatch their eggs successfully, and then, hopefully, band the babies with a tiny little metal bracelet before they fly off.

I tagged along on a mission several years ago to visit one of the Rimrock Ranch boxes where kestrels had successfully laid eggs. This box was considered an “easy one”—you can drive fairly close to it, and it is only six feet or so up a tree. Volunteer Dick Tipton usually checks the Rimrock kestrel boxes, but this time he was nursing an injury. Since time is of the essence with kestrel box checking, in stepped “Team Kestrel” members Ken Hashagen and Nancy and Satch Esperancilla. Once eggs have been found, volunteers must return in the allotted number of days (28-30) to check for babies before they leave the nest.

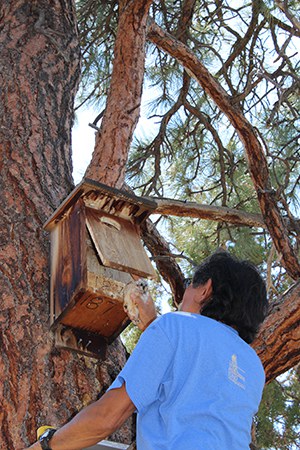

We moved on to the next box, just down the road from Rimrock Ranch on public land. We again parked at a specific juniper tree and got out of the car. Fifty yards off the road, we found the box 15 feet up in a pine tree. Satch expanded his handy folding ladder and climbed up to the box. Success! Two babies squawked anxiously and a mama kestrel called out from nearby. Satch climbed down carefully, handing one baby to Nancy, who handed it to Ken—a licensed bander—who recorded key data like size, sex, and overall health. He then clamped a tiny little silver bracelet on the chick’s leg and the baby was returned to its box.

After all the driving, the checking and banding process seemed quick, but it was unbelievably awe-inspiring. It was truly amazing to hold a tiny baby kestrel, both fierce and fuzzy at the same time. Witnessing the drama drives home the fragility of nature: this little bird could be gone in the wink of an eye, like the ones at Rimrock. We’re determined to see kestrels survive and flourish, which is precisely why we’re so committed to protecting the habitat they need.

Over the years, Team Kestrel has recorded thousands of kestrel fledglings, and it is the efforts of Don, Dick, Satch, Nancy, and Ken that give us all hope for the future of wildlife. Together we can conserve habitat for wildlife and then work to help wildlife return and thrive—whether it is a steelhead or a kestrel. Places like Rimrock Ranch and Whychus Canyon Preserve provide the habitat wildlife need to survive now and into the future, and the Land Trust is dedicated to the long-term stewardship of these lands.

Learn more: