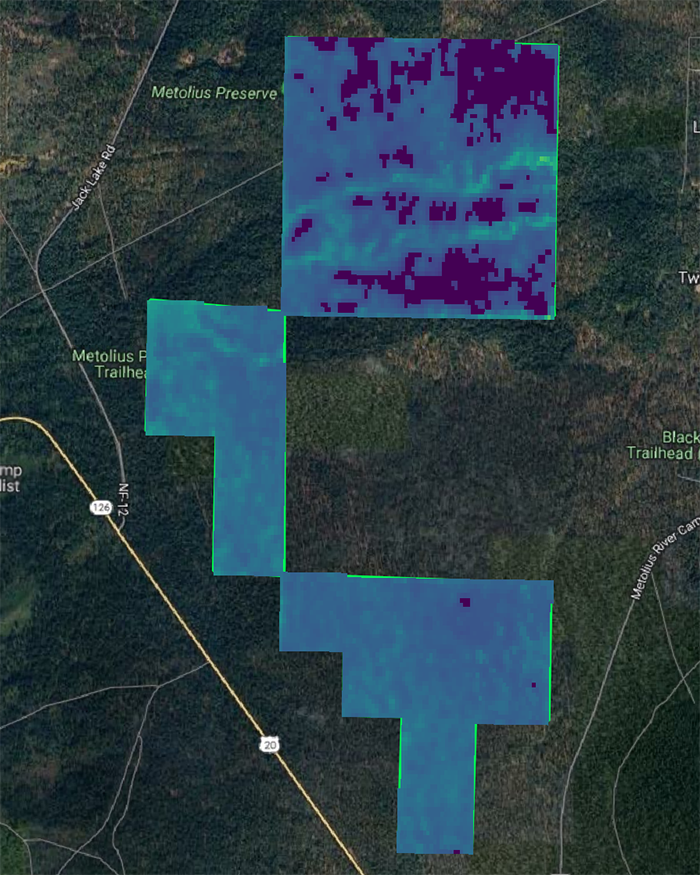

I arrived in Bend in the last week of June, excited to begin my internship with the Deschutes Land Trust. My main task for the summer was to examine and map remote sensing data from the Land Trust’s protected lands to assess trends in carbon storage and canopy cover. I dug into data for places like the Metolius Preserve to see if looking at those trends would help us gauge the success of forest restoration efforts in helping store more carbon at the Preserve.

I sat in the office for hours, cataloging years’ worth of aerial imagery into easily accessible folders before importing them into my mapping software and running calculations. It was deeply gratifying to get the mapping work done. Seeing the maps of carbon storage shift year-to-year was particularly eye-catching, and matching up those shifts to tree thinning and the subsequent recovery was like solving a puzzle, slowly piecing together a picture of the Metolius Preserve’s history.

Seven weeks in, though, I had an experience that put my work behind a laptop screen to shame. I joined Peter Cooper, from the stewardship team, on a monitoring visit at Metolius Preserve. I had tagged along on the stewardship team’s visits to different Land Trust-managed properties before, but this was the first time I would be setting foot on one of the Preserves for which I had been mapping carbon and canopy data.

Bright and early on Monday morning, as we pulled into the northern entrance to the Preserve, I attempted to coax my freshly caffeinated brain to figure out where we were on the maps I had been working with on my laptop so I could compare it to what I was seeing. That effort failed immediately when I stepped out of the car and got a good look at the conifer forest around me. In the still-soft morning sun, now-familiar ponderosa pines rose like pillars into the sky, mixed in with what I had just been taught to identify as Douglas and grand firs. Here and there, the bright green needles of larch trees shone in shafts of sunlight. Below the tallest trees grew younger, denser-leaved members of all four species, and in the open space around the parking lot I could see tiny seedlings, needles still too big for their tiny stems and branches.

As we hiked through the Preserve, Peter checked camera traps and photopoints, and my eye was drawn over and over to the details my mapping data couldn’t capture. Even this late in the summer, the trails were lined with more wildflowers than I could name. Butterflies flitted from plant to plant, while bees trundled amiably around each flower in a cluster before moving on. Tiny wild blackberries swelled from vines like rubies. Oregon grapes (which I didn’t know existed before this visit), impossibly round and tart as gooseberries, were everywhere. The pièce de résistance was when we reached a meadow, incongruous after walking under so many towering trees. On a whim, I checked a trail map, and something tickled my memory. My mind felt like it was expanding as I suddenly made the connection—I’d seen this place before! In my maps, there were patches of low carbon storage with no canopy cover, and I had just walked right through one of them.

As we hiked through the Preserve, Peter checked camera traps and photopoints, and my eye was drawn over and over to the details my mapping data couldn’t capture. Even this late in the summer, the trails were lined with more wildflowers than I could name. Butterflies flitted from plant to plant, while bees trundled amiably around each flower in a cluster before moving on. Tiny wild blackberries swelled from vines like rubies. Oregon grapes (which I didn’t know existed before this visit), impossibly round and tart as gooseberries, were everywhere. The pièce de résistance was when we reached a meadow, incongruous after walking under so many towering trees. On a whim, I checked a trail map, and something tickled my memory. My mind felt like it was expanding as I suddenly made the connection—I’d seen this place before! In my maps, there were patches of low carbon storage with no canopy cover, and I had just walked right through one of them.

With that meadow reference point in mind, I could (roughly) map out the path Peter and I had walked, comparing the impossible diversity of the forest to the numbers that had been dancing on my laptop screen for weeks. They weren’t mutually exclusive—everything I was seeing was encompassed by the carbon values on my maps—but the data didn’t tell me anything about butterflies or bears or blackberries. Here was the missing link between my coursework and the Land Trust’s stewardship efforts: while I sat in a classroom for months on end, analyzing large-scale data sets, the Land Trust took those principles and expanded upon them through their conservation efforts. My maps could never tell the full story of a place. They could tell me the Land Trust was succeeding in helping store more carbon and combat climate change, but they didn’t show the butterflies, bees, or blackberries that also benefit from restoration efforts and the long term protection the land trust model offers to our community.

Learn more:

- About carbon storage at the Metolius Preserve

- Meet Varun Shirhatti

- About the Metolius Preserve Forest Restoration