The Land Trust's forestry efforts at the Metolius Preserve have been focused on creating a forest that is resilient to the impacts of climate change, provides healthy habitat for native plants and animals, and helps protect adjacent neighborhoods from catastrophic fire.

Why do our forests need restoration? Fire is integrally connected to our forests in Central Oregon and removing it for the last 100+ years has dramatically changed the face of our forests. Historically, forests in Central Oregon were diverse, dynamic places. Ponderosa pine/mixed conifer forests, like we have at the Metolius Preserve would have had regular small intensity fires that created gaps in the forest, thinned sick trees, and promoted new growth. More high intensity fires would have also come through, again changing the face of the forest and creating a mosaic of widely spaced trees intermixed with denser clumps of trees. The Land Trust’s forest restoration efforts are working to restore these historic conditions, improve habitat for wildlife, and help our forests be more resilient as our climate continues to warm.

How does forest restoration help climate change? Forest restoration can help relieve trees from overcrowded, resource-limited conditions, so they’re better able to adjust to and survive various forms of natural disturbance (beetles, fungus, mistletoe, periods of drought, etc) that are becoming increasing more frequent due to climate change. Did you know that healthy forests are also considered one of the best forms of natural carbon storage? Trees, and all plants actually, are magical! They make their own food through a process called photosynthesis that involves taking CO2 out of air to make the energy they need to survive. So, trees and forests help mitigate climate change by actively removing CO2 from the atmosphere! Learn more about forest restoration and carbon storage at the Metolius Preserve.

Land Trust forest restoration activities include forest thinning, decommissioning old logging roads, and re-vegetation of closed areas. Major efforts include:

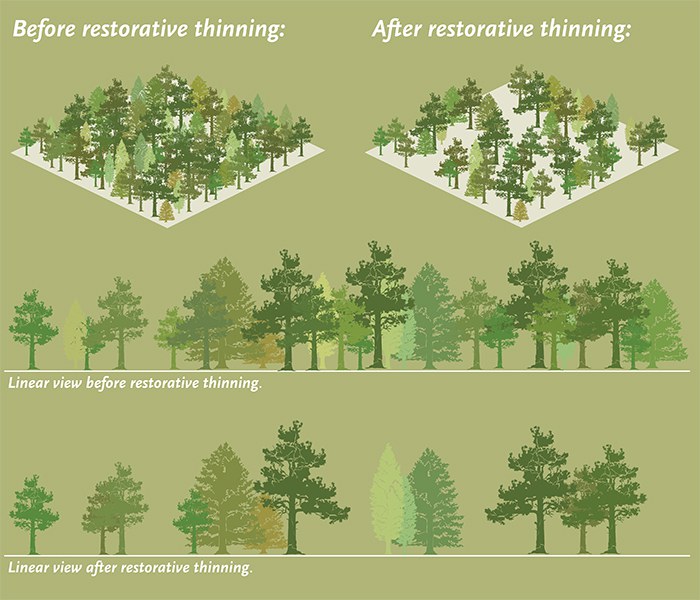

- 2005 and 2006: restorative thinning was completed on 557 acres of 50-60 year old ponderosa pine in the central and southern portions of the Metolius Preserve. Brushing and mowing of slash and understory shrubs followed. An additional 100 acres were hand-thinned along stream corridors. The drawing below shows the type of thinning we completed. Our goal was to create patches of widely spaced trees intermixed with denser clumps of trees and gaps with few trees. This mosaic pattern mimics nature: forests of mixed-age trees with a variety of habitats for wildlife. It also helps improve overall forest conditions and protects neighboring communities by reducing the threat of catastrophic wildfire.

- 2010: 150 acres were hand thinned and piled in the northern section of the Preserve. These piles were then burned and seeded with native bunchgrass seed.

- 2011: 60 acres were mechanically thinned in the northern portion of the Preserve in for white-headed woodpecker study plots. Learn more about this project below.

- Road decommissioning: In 2007, we removed an old road near the South Trailhead to reduce the amount of soil running into Lake Creek and planted more than 7,000 new native plants. In 2008, we worked with partners to remove a culvert and road on Lake Creek, and planted 1,500 new native plants. Other roads at the Preserve have been closed and are re-vegetating on their own.

- 2023: mowing completed to help prepare the Preserve for the return of prescribed fire. Read more about it here.

- 2025: prescribed burn completed on ~48 acres in the northern section of the Preserve. Read more about it here.

Creating Snags for Wildlife

Snags (dead and dying trees) are critical to wildlife. Because the Preserve is snag-deficient, the Land Trust has created numerous snags (approximately 130) across the Preserve and has recruited college students to conduct monitoring of these sites. Snags were created using a variety of methods: cutting the tops off of trees, girdling trees with a chainsaw, and baiting trees with pheromones that attract bark beetles. (Read all about this experiment in our Fall 2008 newsletter.)

Results at the Metolius Preserve and other research sites indicate that the way a tree dies strongly influences its usefulness to wildlife as a snag.

- Trees killed by bark beetles (that are attracted to the tree due to pheromone baiting) are used heavily by foraging woodpeckers as they consume the larvae and adults. This beetle feasting introduces fungi, which soften the outer wood on the snag so woodpeckers can excavate nest and roost cavities.

- Woodpeckers have also been observed excavating cavities and successfully fledging their young from topped trees.

- It appears that girdled trees aren’t utilized as much by wildlife.

Current studies are focused on whether or not white-headed woodpeckers exhibit a preference for snags created by topping vs. baiting and if they prefer to be within a gap (open area) or in the forest matrix (closed canopy). While data collection is ongoing, birds seem to be using trees in the gaps more than the matrix. We’re excited to continue learning about woodpecker activity at the Metolius Preserve and how that knowledge might inform future management.

Learn more:

- About the Metolius Preserve.

- About historic conditions in healthy east Cascade pine forests.

- About the Land Trust's Whychus Canyon Preserve forest restoration.