Thanks for choosing to learn more about the cultural history of Camp Polk Meadow Preserve! Interpretive signs are provided in the following formats:

- Leer en español.

- Download as a PDF in english.

- Listen with an audio reader. (Download PDF first).

Rich Connections to the Land

Camp Polk Meadow has been an important place for people for thousands of years.

Since time immemorial, Native Americans, including the Warm Springs, Wasq’u (Wasco), and Paiute Tribes, have lived in or visited this region. They visited places like Camp Polk Meadow on their seasonal rounds to hunt and gather food and other resources for clothing, tools, and ceremonial uses. Together these Tribes represented four language families with rich community and trading networks. Today, these Tribes are represented by the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. Learn more about Native Americans and Camp Polk Meadow below.

The arrival of Euro-Americans in the 1800’s was devastating to Native American communities. As settlers cleared forests and built settlements, they brought disease and disrupted traditional Tribal territories which led to forced displacement and cultural suppression. By 1834, only a remnant of the robust Native American population remained. Between 1850-1870, the United States government further disrupted lifeways by forcibly moving most Tribes onto established reservations through treaties. The impacts of this displacement are still felt today, but Native American communities are building a strong future through their connection to the land.

The first Euro-Americans began to travel through this area in the early 1800s in search of beaver to trap. By the 1840s-1850s, survey parties were mapping and seeking westward routes. From September 1865 to May 1866, soldiers were sent to what is now Camp Polk to camp and “protect” settlers and travelers on the new road that was being built, the Santiam Wagon Road. In reality the soldiers never encountered Native Americans and instead spent their time building small cabins and helping construct the Wagon Road. The name Camp Polk for Polk County in the Willamette Valley, home to most of the soldiers, would stay with the meadow for generations to come.

In 1868, Samuel Hindman (pronounced Hineman) acquired 160 acres that included Camp Polk Meadow. Then, between 1868–1870, Samuel and Jane Hindman and their three children moved to the western portion of Camp Polk Meadow. The Hindmans maintained the Santiam Wagon Road and managed Hindman Station—a store, post office, and a place to house travelers. Learn more about Hindman Station below.

Native Americans and Camp Polk Meadow

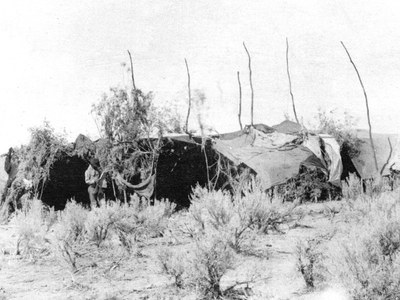

Since time immemorial, Native Americans, including the Warm Springs, Wasq'u (Wasco), and Paiute Tribes, have lived in or visited this region.

Tribal groups including the Wasq’u (Wasco), Tenino, Tygh, Wyam, John Day, Molalla, and Northern Paiute traveled to Camp Polk Meadow on their seasonal rounds. They came from great distances over the mountains, through the desert, and up the Deschutes River to get to Camp Polk and other regional locations. They hunted game for food, clothing, tools, and ceremonial uses. They also speared, netted, and trapped fish in Whychus Creek. At that time, Whychus Creek had plentiful runs of steelhead and Chinook salmon. The first people also came to the meadow to dig roots and tubers. They gathered berries, nuts, flowers, seeds, and other plant material used for food, shelter, baskets, tools, and ceremonies.

Colonization

In the 1800s, disease introduced by Euro-Americans killed many native peoples. By 1834, only a remnant—at most, one-eighth of the pre-contact population—remained. Native people who survived were increasingly separated from the places they knew and their way of life.

Camp Polk was part of the lands forcibly ceded to the United States in 1855 by the Tribes. Under the treaty, the Tribes relinquished approximately ten million acres of land and reserved the Warm Springs Reservation for their exclusive use. The Tribes also kept their rights to harvest fish, game, and other foods off the reservation in their usual and accustomed places.

Today, the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs represent Wasq’u (Wasco), Warm Springs, and Paiute tribes. The Land Trust honors their rights as a sovereign nation to harvest and manage fish, wildlife, and other first foods on their usual and accustomed lands, including Camp Polk Meadow Preserve. We also honor their traditional role as the original stewards of the land, helping care for and connect with the land since time immemorial.

The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs provide funding, technical support, and guidance for conserving and restoring Camp Polk Meadow Preserve. The Land Trust has worked with the Tribes for decades to care for the meadow, including helping support regional long-term efforts to return Chinook salmon and steelhead to the portion of Whychus Creek that runs through the Preserve. We are grateful for their long-term partnership and dedication to the balanced protection, use, and enhancement of natural and cultural resources.

Hindman Station

The Hindman family (pronounced Hineman) played a significant role in the settlement of Camp Polk and Central Oregon.

Between 1843-1845, westward migration began along the Oregon Trail. This migration, tied to the belief that Euro-Americans had a divine right to settle the Western US, had deep and lasting impacts on Native American communities. As settlers cleared forests and built settlements, they brought disease and displaced Indigenous peoples who had their own deep ties to the land. Recognizing and honoring the Indigenous perspective on settlement allows us to appreciate the full historical context of this place.

The Santiam Wagon Road

The Santiam Wagon Road was built in the 1860s to connect the Willamette Valley to the grasslands of Central Oregon and the gold mines of eastern Oregon and Idaho. It followed well-known trails and travel corridors used by Native Americans. It was nearly 400 miles long and served as a livestock trail and freight route over the Cascades from 1865-1939. In 1868, Samuel Hindman purchased 160 acres of land from the Wagon Road Company for $400. His house and barn would become Hindman Station on the Santiam Wagon Road.

Hindman Station was established by Samuel Hindman between 1868-1870 as a stopping place on the Santiam Wagon Road. It was where travelers made their final preparations for trips east across the high desert or west across the Cascades. The Station offered a store for replenishing goods, a post office, and a place to rest cattle and horses. For the Hindman family, the Wagon Road offered an opportunity for barter and some cash to supplement subsistence ranching.

By 1885, a new bridge over the Deschutes River at Tetherow began diverting more traffic via Sisters, bypassing Camp Polk and Hindman Station. The Camp Polk post office moved to Sisters in 1888. By 1900, the Columbia Southern Railroad connected to Shaniko (north of Madras), taking much of the freight traffic—especially wool wagon trains—away from the Santiam Wagon Road. By 1911, the Oregon Trunk Railroad reached Bend, further rerouting traffic and marking the end of the Santiam Wagon Road and Hindman Station.

Hindman Barn

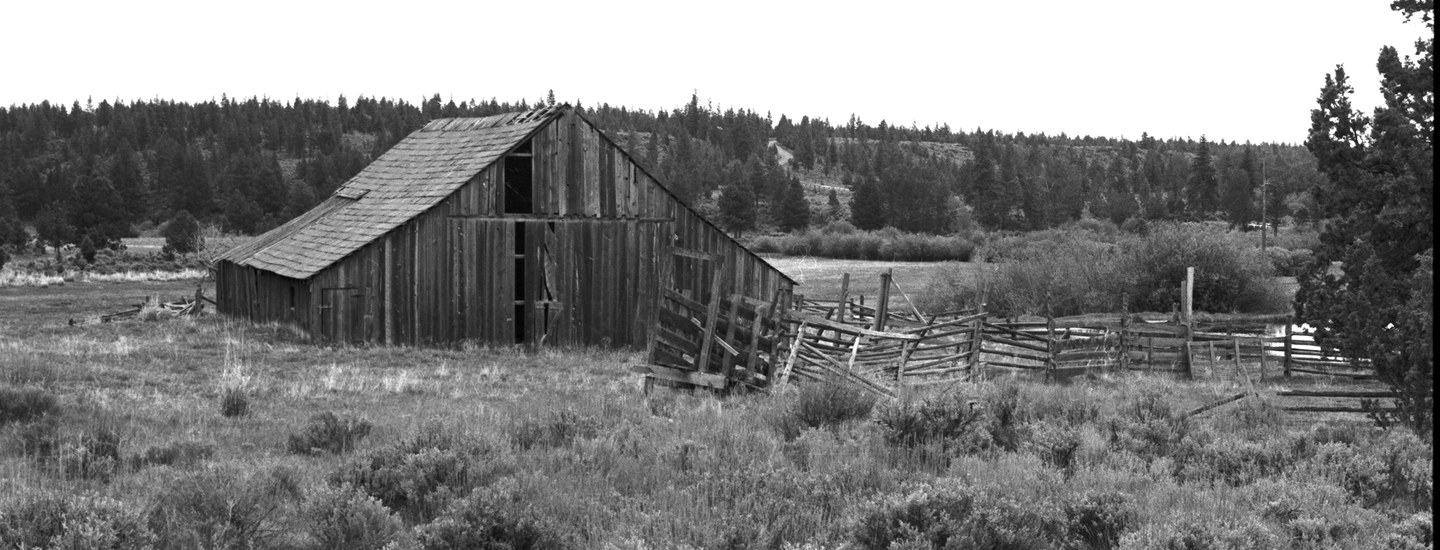

Today, the posts and beams from the Hindman Barn are all that remain of Hindman Station.

The Hindman barn originally measured 75’ long by 50’ wide. The barn was an impressive structure built for permanence and handcrafted by Samuel Hindman who was skilled with axe and timber. A distinctive feature of the barn was the 10 foot wide wagon way that passes north-south through the center of the barn. It allowed hay wagons to be unloaded directly into the loft or other parts of the barn. These blueprints—drawn in 1972 when the barn was still standing—show some of the other construction details and key features.

By 1960, the Hindman barn was no longer used for daily ranching activities and began to deteriorate. A windstorm damaged the already failing roof in 1990, sealing its fate. By the time the Deschutes Land Trust acquired the meadow in 2000, all that remained of Hindman’s barn was the inner core structure.

Hindman Barn Craftsmanship

Since much of the barn was lost over time, construction details are based on the observations of the craftsmanship we see today.

The timbers used to frame the Hindman barn were cut on site. They came from ponderosa pines that were large enough to produce straight heartwood beams 10” square. There are sixteen 14’ tall posts on horizontal sills. The top beams that hold the structure together are 65’ long, hewn from a single log!

The timbers all show signs of a broad axe—not a draw knife, nor an adze. The barn siding, however, was sawn at a mill. At the time, milled lumber could have been hauled from Prineville, the Dalles, or from the Willamette Valley (an eight day round-trip with freight!).

The barn has mortise-and-tenon joints that are secured with wooden pegs called trunnels. Samuel Hindman would have crafted these joints by hand. The kind of joinery and timber framing Hindman used were more sophisticated than the log structures that soldiers and many settlers used.

Hindman Barn Use

The Hindman barn was in active use from 1870–1960, stabling livestock and storing hay.

The barn and homestead served as a stopping place on the Santiam Wagon Road. The Hindmans established a reputation for their hospitality and help to early settlers. Samuel Hindman hauled supplies from the Willamette Valley to sell at Hindman Station. He offered items such as matches, salt, coffee, Arbuckle brand work shirts, and a place to pick up the mail. The Hindmans also sold fresh vegetables from their household garden and from their land on nearby Indian Ford Creek.

The Hindman House

The Hindman House sat south of the Hindman barn and was surrounded by pastures.

Samuel and Jane Hindman and then their children Charley, Sarah, and Daniel, lived in the house starting in 1868. This was in the early days of Euro-American settlement, and neighbors were few and far between. Stories from travelers, experiences with wildlife, talk about their own animals, and chores likely broke the overwhelming stillness. Life revolved around essential needs: food, shelter, and safety. The Hindmans adapted to scarcity and made do without many things.

Reconstructing the Hindman House

The Hindman house, much like the Hindman barn, lacks detailed written descriptions. The house was probably built of log and milled lumber that was added onto over time. We know that it was located on the Santiam Wagon Road, 125 feet north of the current Camp Polk road, near the edge of the wetland. According to Samuel Hindman, the house was situated over “a good spring of water right under the house in the cellar.” Later inhabitants would use the cellar under the kitchen to keep dairy products fresh. Today, the root cellar cooled by the springs is all that remains of the Hindman home.

In 1902, Samuel’s son Charley married Martha Taylor Cobb and both lived at Camp Polk in the Hindman house. Martha managed the Hindman ranch until her death in 1940. In 1947, the Cutsforth and Mahaffey families purchased the Hindman ranch and moved into the Hindman house. By 1960, the house had deteriorated to the point where it had to be demolished.

Hindman Springs Today

Today, nature plays a leading role at Camp Polk Meadow Preserve.

The Hindman Springs Area is also a biologically rich part of the Preserve. Wetlands fed by underground springs that come to the surface in this location provide homes for wildlife. They also help clean and filter our water, and mitigate the impacts of climate change by storing carbon. The Hindman Springs Area is a great place to watch birds and where you can see a major native plant restoration project evolve.

Sources:

Adapted and reprinted with permission from Martin Winch’s Biography of a Place.

Thank you!

Many thanks to the following for their help with this Camp Polk Meadow history project: The Oregon Community Foundation Oregon Historical Trails Fund, the Roundhouse Foundation, and private donors. Martin Winch and his amazing book Biography of a Place. Carol Wall for researching and sharing the Hindman family story with our community. Jan Hodgers for sharing her personal photos of the Hindmans at Camp Polk Meadow. Ed Barnum for sharing his original architectural drawings and photos of the Hindman Barn. The Deschutes County Historical Society and Bowman Museum for help with research and photography.