My Life on Trails with John Schubert

Thanks to those of you who came out to our January 31st Nature Night, My life on trails. It was a great presentation full of fascinating information from trails specialist John Schubert. Enjoy the slides from John's presentation below. Then, scroll down for links to resources provided by John about trails, trail etiquette, and how to get involved locally.

If you have trouble viewing the slides below, click here.

Additional resources suggested by John Schubert:

- How to travel lightly on trails: Leave No Trace: www.lnt.org

- Insight into how animals think: Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel, by Carl Safina

- History of Central Oregon roads, trails and more: New Era, by Jarold Ramsey. Biography of Place: Passages through a Central Oregon Meadow, by Martin Winch (available for purchase at the Deschutes Land Trust: 541-330-0017).

About John Schubert:

John Schubert is a retired trails specialist with the Deschutes National Forest. During his 30 years based in Central Oregon, John designed and supervised construction of many well known local trails including Alder Springs, Tumalo Creek, and upper Whychus Creek. John holds a B.A. from Middlebury College and leads trail building workshops in National Parks and Forest around the country. In his spare time, John, a life-long naturalist, explores the remote corners of Oregon by foot, kayak, ski, and bike, always with books, camera, Irish whistle, and friends to keep him company.

The Oregon spotted frog with Jay Bowerman

Thanks to those of you who came out to our February 22nd Nature Night on the Oregon spotted frog. It was a great presentation full of fascinating information about this little frog and it's habitat presented by biologist Jay Bowerman.

Enjoy the slides from Jay's presentation below. Then, scroll down for links to resources that will help you learn more about the Oregon spotted frog.

If you have trouble viewing the slides below, click here.

Additional Resources:

Oregon spotted frog information from US Fish and Wildlife Service

Amphibians of Oregon, Washington and British Columbia: A Field Identification Guide

How to catch a bullfrog

More information on protecting the species

Jay Bowerman

Jay Bowerman holds a M.S. in biology from University of Oregon where he studied salamander chromosomes. After 20 years as the executive director of the Sunriver Nature Center, Jay has returned to biological research that focuses on amphibian ecology. He is the author of more than twenty journal papers ranging from amphibian deformities to leeches. In recent years Jay has focused on mentoring young scientists while continuing studies of western toads, Oregon spotted frogs, and the impact of introduced species, especially bullfrogs, on native amphibians. In his spare time Jay and his wife Teresa stay involved in a variety of local cultural events such as the Wheeler County Bluegrass Festival and the Hoedown for Hunger at Bend's Community Center. Most recently they have been learning to be grandparents.

Black Bears with Dana Sanchez

Thanks to those of you who came out to our March 22nd Nature Night, Behind the Scenes With Black Bears. Dana Sanchez gave a great presentation full of fascinating information about black bears and their habitat, and what we can do to avoid human-bear conflict in urban and backcountry areas.

Enjoy the slides from Dana's presentation below. Then, scroll down for links to resources that will help you learn more about black bears and how to keep them safe.

If you have trouble viewing the slides below, click here.

What can you do to keep bears safe and avoid human-bear conflict? (see the resources below for more ideas)

- Keep pet food indoors. Feed pets in the house, garage or enclosed kennel.

- Hang bird feeders from a wire at least 10 feet off the ground and 6 to 10 feet from the trunk of tree.

- Remove fruit that has fallen from trees.

- Take garbage with you when leaving your vacation home.

- Keep barbecues clean. Store them in a shed or garage.

- Store livestock food in a secure place.

Additional Resources:

- Living with Wildlife - Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife page on black bears

- Tips for recreating in bear country, Oregon Wild

- Recognizing bear sign, North American Bear Center

Books about tracking wildlife:

- Mammal Tracks & Sign; A Guide to North American Species, by Mark Elbroch.

- Wildlife of the Pacific Northwest; Tracking and Identifying Mammals, Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians and Invertebrates, by David Moskowitz.

Dana Sanchez

Dana Sanchez is an Associate Professor of Fisheries and Wildlife and an Extension Wildlife Specialist at Oregon State University in Corvallis. She holds a PhD in natural resources from the University of Idaho and her research focuses on North American mammals from the very small to the very large. Dana also explores the effectiveness of online learning and how to broaden participation in science professions among members of underrepresented groups. Dana has lived in the West most of her life and in her spare time enjoys gardening and training her dog, a Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever.

Learn more about Central Oregon Wildlife:

The Great Basin Spadefoot

Although Central Oregon's high desert doesn't seem like the kind of place where you'd find moisture-loving amphibians, there is in fact one species native to our dry sagebrush country. It's the arid-adapted Great Basin Spadefoot (Spea intermontana).

Ten Facts about Golden Eagles

What bird dives at speeds up to 200 miles per hour, soars on afternoon thermals, and generally mates for life? The golden eagle! In honor of the golden eagle couple Petra and Rocky, who have a nest at the Land Trust’s Aspen Hollow Preserve, here are 10 fun facts about this majestic bird’s nests and courtship:

1. Golden eagle nests are on average 5-6 feet wide and 2 feet high, weighing hundreds of pounds.

2. The largest golden eagle nest on record was 20 feet tall and 8.5 feet wide!

3. Nests are made up of sticks and vegetation. This may include conifer boughs, grasses, barks, leaves, mosses, lichen, fur, bones, antlers, and human-made objects (like wire and fence post).

4. Sometimes, golden eagles will bring herbs/aromatics into their nest. It is believed this may keep bugs away.

4. Sometimes, golden eagles will bring herbs/aromatics into their nest. It is believed this may keep bugs away.

5. Golden eagles may inhabit the same nest for years, or alternate between different nests.

6. New nest material is added every year.

7. Both parents will incubate the eggs, but it is mostly done by the female.

8. Generally, the adult male delivers most of the food to the nest, while the adult female usually feeds the young.

9. Courtship rituals include circling and shallow dives at each other.

10. Nests are mostly built on cliff edges, although they can also be found in tall Ponderosa Pines and very rarely on electric transmission towers.

Learn more:

Little Boa of the Northwestern Woods

Boas are the victims of bad press. Public perceptions about these snakes have been shaped by too many old, grade-B safari movies with plots revolving around one frightening jungle menace after another. Many directors seemingly can't resist using the image of an immense snake dropping from a tree to envelope some unfortunate actor in its deadly coils.

Don't automatically believe all snake-related depictions that you see in the movies. It's a lesser-known fact that there are also a number of small boa species. One is native to Central Oregon and most of the surrounding Pacific Northwest region, along with the wooded sections of California. This harmless little snake, which usually does not grow much beyond two feet in length, is called the rubber boa (scientifically known as Charina bottae). The common name is derived from the loose, rubbery quality of its smooth, olive-brown skin.

While its elastic skin alone would qualify it as unique, the rubber boa has a couple other quirky traits that make it one of the most intriguing of our native reptiles.

One rather odd characteristic of this slow-moving, thick-bodied snake is the bluntly rounded tail that bears a remarkable resemblance to a secondary head. Consequently, the rubber boa is sometimes called the "two-headed snake" or "double-ender." The snake uses this fake head to its advantage when confronted by danger. Shy and retiring by nature, a rubber boa will not bite to protect itself. Instead, it simply rolls into a tight ball, hides its head beneath the coils of its body, and then displays the tail as a decoy "head." Occasionally, a rubber boa will even jab about with the tail, simulating a striking movement. In this way a predator is attracted to the more expendable tail, while the actual head is protected from harm. The tip of the tail features a large, solid scale plate that creates a protective hard cap to deflect the bites of attacking animals. Additionally, a bad-smelling musk is emitted to repel enemies.

Because most kinds of boas are tropical, the rubber boa bears the distinction of being the most northerly ranging of all its family. It reaches the limits of its distribution in mid British Columbia, Canada. Although rubber boas occur throughout all but the most arid deserts and damp, shady coastal rain forests of the Northwest, it's very secretive and rarely seen. Most of the daylight span is spent beneath logs and rocks, in rodent tunnels, or burrowing in leaf litter. As evening shadows lengthen or during cloudy mild weather, the little boa creeps from its hiding place to search for food. On warm summer nights it may continue to hunt throughout most of the nocturnal hours. The rubber boa eats a variety of small animals, including such items as lizards, other snakes, insects and nestling birds (it's a good climber), but the primary favored food source is small rodents. It's particularly fond of young mice that are still in the nest, using its all-purpose blunt tail to fend off attacks by mother mouse. In typical boa fashion, prey is subdued by constriction. Two or more loops of the snake's body are quickly wrapped tight around the victim, the intense compression causing death from suffocation and heart stoppage.

Like all other boa species, rubber boas are "live-bearing" (viviparous). One to eight young are born in the late summer or early autumn. Baby rubber boas are about seven inches in length and have a pleasing pinkish-tan hue. In fact, these dinky infant boas can sometimes initially be mistaken for a similarly colored earthworm.

Hiking in Deschutes Land Trust Preserves and just about anywhere else in the Bend area offers a possible encounter with a rubber boa. It inhabits not only the pine forested slopes of the Cascades (especially the borders of meadows where there are rotting logs for cover), but also eastward into the semi-arid juniper woodlands. Although not truly a desert reptile, rubber boas have been found in crevices at Fort Rock amid the sweeping sagelands.

Learning about this interesting and often overlooked animal can add a broader dimension to one's appreciation of the outdoors. Should you chance upon a rubber boa during your next jaunt along a trail, slow down for a close look and make a new acquaintance. Being slow-moving and non-flighty, probably no other snake is easier to get to know than our gentle little boa of the Northwestern woods.

Other Land Trust blog posts by Alan St. John:

About Alan St. John

A native Oregonian, Alan D. St. John lives in sage-scented juniper woodlands near Bend with his wife, Jan. Al is a freelance interpretive naturalist who uses writing, photography, and drawings to teach about the natural world. Specializing in herpetology, he has worked as a reptile keeper at Portland's zoological park, and conducted extensive reptile and amphibian field surveys for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, USDA Forest Service, the U. S. Department of the Interior's Bureau of Land Management, and the National Park Service. Along with authoring the books, Reptiles of the Northwest and Oregon's Dry Side: Exploring East of the Cascade Crest, his work has appeared in National Geographic, Outdoor Photographer, Ranger Rick, Natural History, Country, Nature Conservancy, The New York Times, and other periodicals.

Bats of Central Oregon

Summer is prime time to view bats out and about in Central Oregon! So grab your chair, set up at dusk, and to see what's flying. Our native bats eat insects--several hundred a night--so head to some place where the insects fly. Lakes can be a hot spot since bats will drink and hunt for insects there. But, your local street corner or your front porch will also do since the street/porch lights will attract insects. Then, be patient and quiet. You'll often hear the chirping of a bat before you'll see it. When you do see one, you'll need some background on our local species. We are here to help!

We asked National Park Service ecologist, Tom Rodhouse, for some local species to watch for and here is his list:

- Spotted bat (Euderma maculatum). The spotted bat is a favorite because it has huge pink ears and three large white spots on its back against a black background. Rarely seen or captured by biologists during surveys, the spotted bat is a desert dweller that roosts only in really large cliffs along desert canyons and open forest meadows, and flies high, chasing down large moths. It can be heard during its foraging bouts at night by its tell-tale chirping or clicking calls that are audible to the unaided human ear--unique among Oregon's bats. Learn more about spotted bats.

Spotted Bat. Photo: Michael Durham.

Spotted Bat. Photo: Michael Durham. - Pallid bat (Antrozous pallidus). The pallid bat is one of central Oregon's largest bats and specializes on capturing crickets, scorpions, and centipedes. It has huge ears like the spotted bat but is otherwise distinctive because its fur is a yellow tawny color. Pallid bats are also desert specialists and are very social, forming large maternity colonies in the desert canyon cliff walls. Learn more about pallid bats.

Pallid bat. Photo: Michael Durham.

Pallid bat. Photo: Michael Durham. - Canyon bat (Parastrellus hesperus). The canyon bat, formerly called the western pipistrelle, is the smallest bat north of Mexico. It too is a desert dweller that comes out early in the evening so it is frequently seen flitting about chasing small flies and mosquitoes in, of course, desert canyons. It can sometimes be seen during the day along the lower Deschutes and John Day rivers sneaking out of its cliff crevice roost for a quick drink. Learn more about canyon bats.

Canyon bat. Photo: Michael Durham.

Canyon bat. Photo: Michael Durham. - Hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus). The hoary bat is the largest bat in Oregon and is migratory, arriving the region in spring and departing in fall, rather than staying to hibernate. The hoary bat is a very strong, fast flying bat that sometimes can be seen chasing other bats (although not to eat them, it too is an insect eater). Hoary bats are unique because they roost in the foliage of cottonwoods and other deciduous trees. They are not desert specialists but do frequent desert canyons as well as the west-side forests of Oregon. Learn more about hoary bats.

Hoary bat. Photo: Michael Durham.

Hoary bat. Photo: Michael Durham. - Little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus). The little brown bat has been considered America's most widespread and common bat. However, in recent years this perception has been forcibly changed as little brown bat populations in eastern North America have been decimated by the bat disease white-nose syndrome. So far, little brown bats in Oregon appear not to have been infected by the disease although it has spread in to Washington so it may only be a matter of time. Little brown bats are one of several plain brown bats with indistinct markings that live in Central Oregon. Little brown bats are commensal with humans, meaning that they will share our residences, sometimes roosting in attics, or hanging out under porch eaves while resting in between foraging bouts. Learn more about little brown bats.

Little brown bat. Photo: Michael Durham.

Little brown bat. Photo: Michael Durham.

Learn more about:

- The role bats play in nature: pest control, pollination, seed dispersal and more!

- Reasons bats are cool!

- Get involved with bat conservation.

Coming Home to Central Oregon

On September 28th, the Land Trust hosted a Nature Night talk with scholar and writer John Elder. John spoke about sense of place--a phrase often used to describe the ways in which a given landscape's geology, climate, forest history, indigenous culture, and patterns of settlement can all influence the experience of living there.

Referencing writers from Jarold Ramsey to William Wordsworth, John wove a story about how we can truly affiliate with a place. Affiliation is "a more active and conscious process of claiming a place as one's own." It means you make the place you live a part of your family. You connect on a personal, emotional level and have an ethical obligation to make your place better.

John finished his talk with a reading from Gary Snyder's Turtle Island. A simple message for how we go forward:

stay together

learn the flowers

go light

John Elder's suggested readings:

- George W. Aguilar, Sr., When the River Ran Wild! Indian Traditions on the Mid-Columbia and the Warm Springs Reservation, University of Washington Press, 2005

- Willa Cather, Death Comes for the Archbishop, Knopf, 1927

- Jarold Ramsey, New Era: Reflections on the Human and Natural History of Central Oregon, Oregon State University Press, 2003

- Leslie Marmon Silko, "Landscape, History, and the Pueblo Imagination," pdf from The Norton Book of Nature Writing

- Gary Snyder, Turtle Island, New Directions, 1974

- Martin Winch, Biography of a Place: Passages through a Central Oregon Meadow, Deschutes County Historical Society, 2006

About John Elder

About John Elder

John Elder taught English and Environmental Studies at Middlebury College in Vermont for almost four decades. He continues to teach at the Bread Loaf School of English and the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference and to give frequent talks about environmental topics and nature writing. John holds a PhD in English from Yale University and has received many honors and awards for his teaching and writing. John is also a widely published author with a host of essays and books. Three of his recent books—Reading the Mountains of Home, The Frog Run, and Pilgrimage to Vallombrosa—combine landscape description and discussions of literature with memoir. In 2016 he published a "musical memoir" about immersion in Irish music called Picking Up the Flute. He is also co-editor of The Norton Book of Nature Writing. John, with his wife Rita and the families of their two sons, helps to run a maple-syrup operation in the hills of Starksboro, Vermont.

El Niño vs. La Niña in Central Oregon

If you’re an outdoorsperson of any kind, hearing “El Niño” or “La Niña” probably elicits a feeling within you, for better or worse. In a bizarre popularization of an otherwise technical meteorological term, it seems that anyone with a vested interest in winter weather has an opinion on El Niño and La Niña, but what are these two phenomena in the first place, and what do they mean for this winter in Central Oregon?

On November 9, 2017, the National Weather Service predicted a 65-75% chance of a “weak La Niña” for winter 2017-2018. This prediction follows a relatively short 2016-2017 La Niña and a 2015-2016 El Niño that was one of the strongest in history.

To understand either El Niño or La Niña—Spanish for “the little boy” and “the little girl,” respectively—you first have to take a dive into the oceanic system known as El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO.

ENSO is constant, and you can think of it as warm water sloshing back and forth—or oscillating—very slowly across the Pacific Ocean. El Niño and La Niña are just specific ENSO scenarios that can determine which direction the water sloshes in a given year.

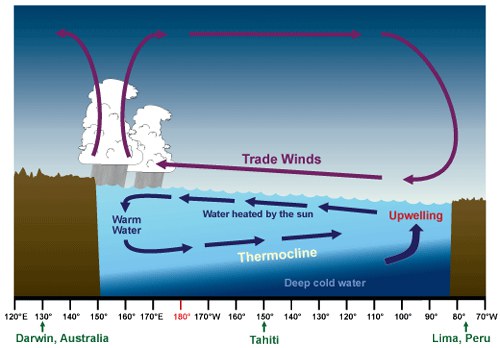

- In a normal year (image below), easterly trade winds (winds that blow from east to west) carry warm air from the Americas toward Asia. This piles up warm water on the west side of the Pacific, which allows cold, deep water to rise to the ocean’s surface along the coasts of South, Central, and North America. This is known as upwelling, and the cold water brings with it important nutrients that contribute to coastal ecosystem and fisheries health, particularly in South America.

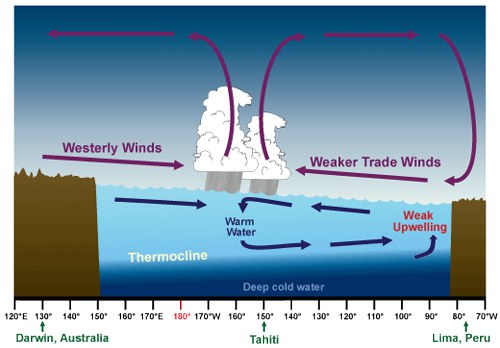

- In an El Niño year (think the winter before last), the normal ENSO pattern reverses as pressure changes in the western Pacific and surface sea temperatures increase at least 0.5ºC above a normal year (see image below). These changes weaken trade winds and allow more warm water to stay near the Americas. The warmer than average temperatures devastate fish populations in Peru and Ecuador, create big surf all along the coast, and lead to increased precipitation (and incredible skiing) in California’s Sierra Nevada range.

As for Oregon, El Niño usually brings warmer than average temperatures across the state, and particularly in the Cascades. While this isn’t a death sentence for ski season, it’s usually an indicator of less-than-desirable snowfall.

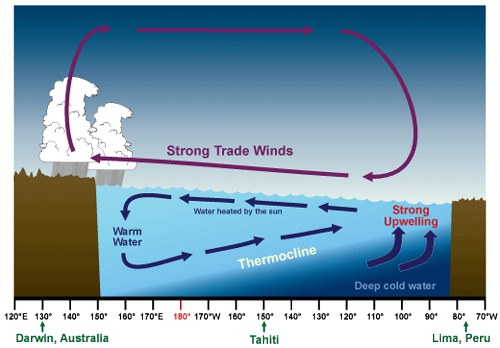

- La Niña events, by contrast, basically enhance all of the components of ENSO. Easterly trade winds become even stronger, leading to increased upwelling along the Americas and an average sea surface temperature drop of at least 0.5ºC. While it’s too early to know exactly how La Niña will impact Oregon this year, La Niña generally does increase the chances of heavy storms and precipitation, particularly in the Cascades.

Remember last winter in Bend? Yeah, that was La Niña.

So, whether you’re hoping for snowpack to support spring stream flows and fish health, or you just want to make sure that the Bachelor season pass you bought in September will ultimately pay off, La Niña could bring much to be thankful for this winter.

Learn More:

- The basics of El Niño and La Niña.

- Effects of El Niño Southern Oscillation in the Pacific Ocean.

- Forecasts for winter 2017-2018 in Oregon.

Winter isn’t coming

On November 18, Mt. Bachelor had its earliest opening day since 2006, much to the excitement of thousands of Central Oregonians who got in some rare pre-Thanksgiving frontcountry turns. Then, just a few days later, a storm rolled in, carrying with it the promise of extensive, Cascades-blanketing precipitation.

There was only one problem: it was the wrong type of storm for snow sports, and rain was the only kind of blanket draping the Cascades.

In one fell swoop, the rain wiped out roughly half of the snow that had built up on Mt. Bachelor, Tumalo Mountain, Broken Top, and the Three Sisters. Even from Bend you could tell that the peaks had reverted back to their autumnal state of exposed rock. At lower elevations, the runoff that resulted from the rain-on-snow event created torrents in the streams and rivers that flow from the Cascades.

Winter, it seemed, had come and gone in a flash flood, getting off to a false start that may become an increasingly common phenomenon in the years to come. In fact, as the impacts of climate change continue to unfold across the planet, the Cascades may offer a window into a future with less snow, more rain, and warmer temperatures.

Now, you might be thinking, “Wait, did she just say more rain? I thought climate change was going to create a drought-ridden desert apocalypse surrounded by mile-high oceans!”

Before you let yourself sink too deeply into that particular doom-and-gloom scenario, though, there are a couple of Central Oregon-specific climate change predictions to know about.

Most climate change models—mathematical characterizations of atmospheric, terrestrial, and oceanic interactions—predict that temperatures will increase in the Pacific Northwest, but these models to not fully agree on how precipitation will change. Where models do mostly agree is that climate change will cause snowfall to decline in the Cascades and throughout the rest of Oregon.

There are a couple of possible reasons for this. The first is intuitive: as a rule of thumb, warmer temperatures mean less snow. Therefore, more precipitation will fall as rain at high elevations, reducing snowpack causing melting. Compounding this is a meteorological phenomenon called atmospheric rivers, which carry masses of warm tropical water to the Pacific Northwest and result in storm events that often lead to flooding and other extreme outcomes. Without the cold temperatures needed for snow, atmospheric rivers lead to large rain or rain-on-snow events in the Cascades that will occur more frequently and in greater magnitude with climate change.

Changing Winds, Less Rain

The second reason for a future with snow-free winters takes us much deeper into the climate science weeds: some research suggests that mountain ranges like the Cascades will actually receive less precipitation overall, in part due to decreased wind speed. So how does wind have anything to do with how water falls out of the sky?

In general, westerly winds—which blow from west to east over the Pacific Ocean—push air toward the Cascades. As the air rises it cools rapidly, causing water vapor to condense and release precipitation that normally falls as snow during the colder winter months. Climate change, it turns out, has been decreasing the speed of winds, which rely on temperature gradients to form. Since northern latitudes heat up more quickly than equatorial latitudes, the temperature differences that normally generate wind in the Pacific Northwest are getting much smaller. With less wind, fewer storms make it up into the Cascades, meaning there is less mountain precipitation overall.

Beyond the Cascades

The effects of decreased snowpack don’t stop on the slopes, though. Our rivers depend on snowmelt for summer streamflows and cool temperatures that support fish and other species. Central Oregon’s water storage systems also rely on snowmelt and streamflow timing to properly fill reservoirs, enable agricultural irrigation, and provide adequate drinking water to cities and towns.

The sad reality is that many of these precipitation changes are already visible throughout the Cascades, and by the 2080s Oregon will likely be rain-dominant.

However, don’t lose all hope for mountain snow just yet. The worst of these trends are still to come, so acting now to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to conserve mountain ecosystems can help keep our ski season intact longer.

Learn more:

- About El Niño vs. La Niña in Central Oregon

- A NASA primer on climate models.

- How climate change affects wind.

- Information on atmospheric rivers.

- How climate change will impact Oregon: The Third Oregon Climate Assessment Report